What was Silk Road?

Silk Road was an anonymous e-commerce website like Amazon and eBay, but with an emphasis on user security and privacy. It used two key pieces of technology to this end: Tor and Bitcoin. Tor is a global network of computers that routes internet traffic in a way that is nearly impossible to trace. It allowed users to connect to Silk Road without revealing their identity or location and without their internet providers knowing about it. The cryptocurrency Bitcoin, little known at the time, allowed Silk Road users to pay or be paid for the goods listed on the site while staying anonymous.

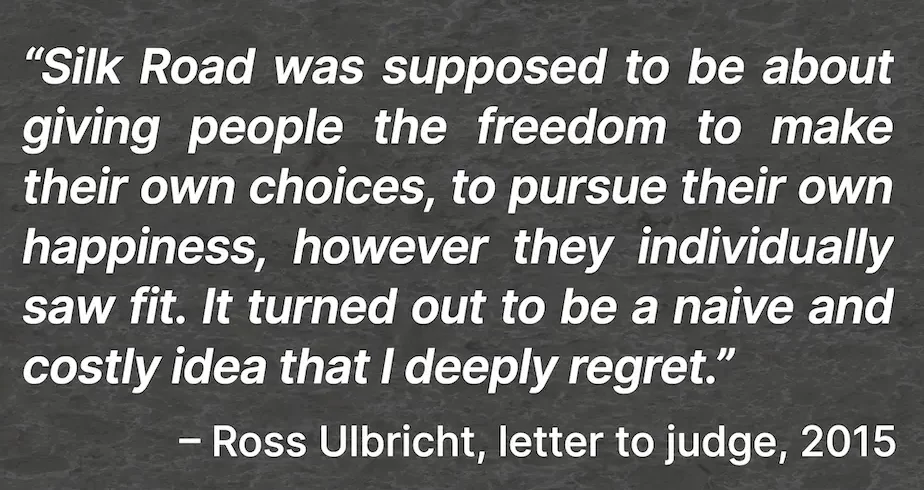

Ross Ulbricht was 26 years old when he launched Silk Road as a free market economic experiment. An idealistic libertarian and entrepreneur, passionate about free markets, individual freedoms and privacy, he believed at the time that “people should have the right to buy and sell whatever they wanted, so long as they weren’t hurting anyone else.” Read his letter [PDF] to the judge.

Many vendors quickly realized that Silk Road’s anonymity made it an ideal platform for selling illegal drugs (the most common transaction being for personal use amounts of cannabis. See Carnegie Mellon University Study below).

Ross did not store, transport or have any contact with the items that were sold on the Silk Road website.

“Over countless hours, I have searched my soul and examined the misguided decisions I made when I was younger. I have dug deep and made a sincere effort to not just change what I do, but who I am. I am no longer the type of man who could break the law and let down so many.”

– Ross Ulbricht in letter to the president [PDF]

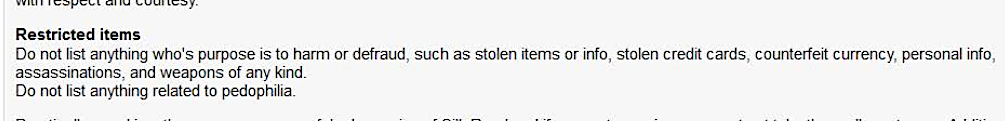

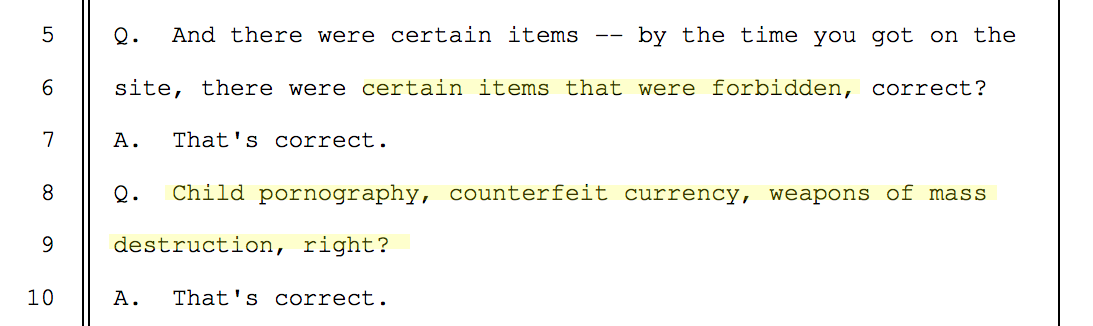

Based on the libertarian non-aggression principle, Silk Road allowed consenting people to voluntarily buy and sell what they chose, as long as no third party was harmed. Despite what some media falsely reported, Silk Road had rules and some listings were prohibited, including stolen items, child pornography, counterfeits, and generally anything used to “harm or defraud” others.[1][2]

Weapons were only allowed on Silk Road for a brief period of time at the beginning (none of Ross’s charges are related to the distribution or sale of weapons). No evidence that actual gun sales occurred was introduced by the prosecution.

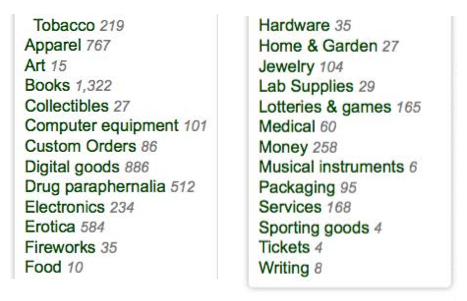

Silk Road had over 20 legal categories, and legal items such as original books, antibiotics, art, clothing and electronics were available.[3]

“There were zero guns on the site…It was one of my jobs to take that stuff down.”

(trial exhibit 132)

“The quantities being sold are generally rather small (e.g., a few grams of marijuana)” (p.12)

“‘Weed’ (i.e., marijuana) is the most popular item on Silk Road” (p.8)

“Silk Road appears to have more inventory in ‘soft drugs’ (e.g., weed, cannabis, hash, seeds) than ‘hard drugs’ (e.g., opiates)” (p.8)

- Surfing the Silk Road: A study of Users’ Experiences.

- Silk Road, the Virtual Drug Marketplace: A Single Case Study of User Experiences.

- Responsible Vendors, Intelligent Consumers: Silk Road, the Online Revolution in Drug Trading.

In stark contrast with Ross’s sentence, the creator of Silk Road 2.0 was given 64 months in the U.K. and the co-owner, an American citizen arrested in 2014 on the same charges as Ross’s, was released after spending just 13 days in U.S. custody. He faced only tax evasion charges and served no prison time. Read more at Sentencing Disparity.

References

- ▲[1] – Silk Road Seller’s Guide (page 5, trial exhibit 120)

- ▲[2] – Trial transcript, day 3 (page 462)

- ▲[3] – Legal categories listed on Silk Road as of October 1, 2013 (trial exhibit 132)

- ▲[4] – Trial transcript, day 3 (page 462)

- ▲[5] – Academic study by Marie Claire Van Hout and Tim Bingham (“‘Silk Road’, the virtual drug marketplace: A single case study of user experiences,” page 6)

- ▲[6] – Academic study by Marie Claire Van Hout and Tim Bingham (“Responsible vendors, intelligent consumers: Silk Road, the online revolution in drug trading,” page 1)

- ▲[7] – Pre-sentencing letter from Joshua Dratel to the judge – May 15, 2015 (page 4)

- ▲[8] – Department of Justice press release – November 6, 2014 (“Operator of Silk Road 2.0 Website Charged in Manhattan Federal Court”)

- ▲[9] – Forbes article, August 11, 2016 (“Illicit Online Drug Sales Triple In Absence Of Silk Road”)